Note: This is a feature story I wrote as a reporter for The Daily World newspaper in Aberdeen, Wash., in the mid-90s. The Sunday "Profiles" feature was assigned to a different reporter every week, so that each reporter did one of these types of articles every 2 months.

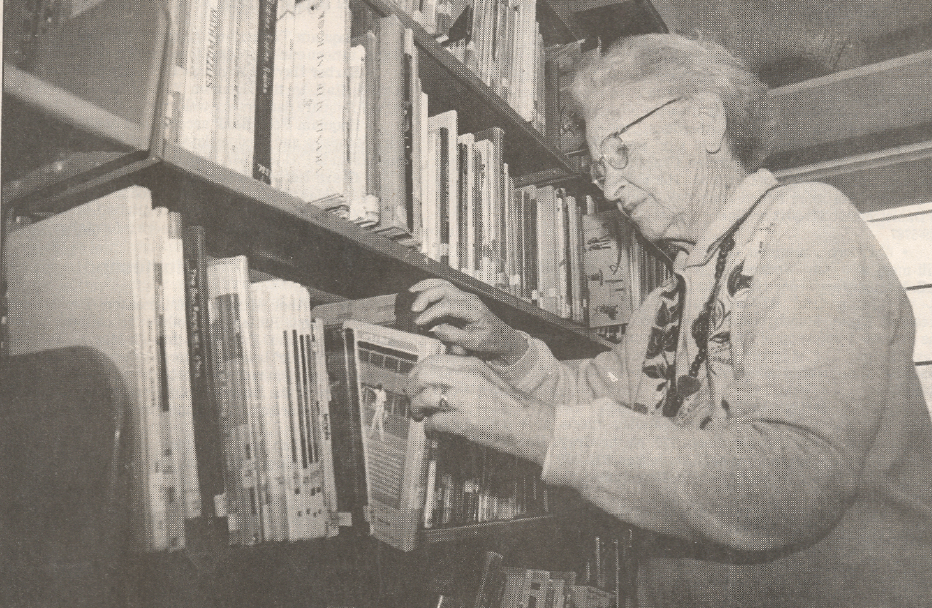

Bessie Hall checks books on the shelves at the Alexander Young Elementary library.

By Matthew Hoy

Special Sections editor

Bessie Hall claims the way to stave off Alzheimer's disease is two-fold: reading books and being around children.

"I do feel that as long as I work in the libraries, and with the kids, that I'm warding off Alzheimer's," said Hall, who will turn 87 this Friday. "These grade school libraries need all the help they can get."

For the past 45 years, Hall has spent countless hours inside the libraries at A.J. West and Alexander Young elementary schools investing her time in getting youngsters to read.

"I used to be able to last a day, but now I just last half-a-day, because old age is catching up on me," she said. "Forty years, off and on. Isn't that a long time now?"

Though she no longer drives, walking the few blocks from her modest Aberdeen home to Alexander Young elementary is no problem for the grandmother of two.

Hall leans back in her recliner and throws a leg over one of the chari's arms, as she talks about everything from children to books, the Great Depression and World War II.

"Those were two very, very important eras that I'm really happy I lived through," she said. "I've had a good life, a really good life."

HALL WAS BORN May 9, 1910 in Custer, S.D. to Henry and Grace Parks. The family lived in Montana for a time before moving to Aberdeen in 1922.

"When my father saw water underneath the houses, he was ready to leave and return to Montana. He was sure there would be mosquitoes and malaria," Hall said, letting out a raucous laugh. In 1928, she graduated from Weatherwax High School. Her 69th high school reunion is coming up.

"Right now, at 69 years, everybody that comes has somebody bringing them," she said smiling.

After graduation, Hall got a job working for the telephone company—a job she enjoyed, though it wasn't her first choice.

"We had a friend who was chief operator up at the telephone office, and there were three of us who chummed together," Hall recalled. "She told us she wanted the three of us to get up there and put our applications in. We did not want to go to the telephone office, but, in that day and age there were no jobs. So we went and put our applications in.

"But our other friend, she applied for a waitress job at Saginaw (Logging Co.) cookhouse," Hall said. As the friend worked around all those loggers, "oh, we envied her," Hall added.

BY THE TIME World War II had started, Hall was a supervisor at the local telephone company office and her husband, Alexander Hall, was in the Marine Corps stationed in Seattle.

"The telephone office was the hot spot because we had troops all up and down the coast," she said. With the attack on Pearl Harbor, fear of a possible Japanese invasion on the mainland was widespread, prompting the military to post soldiers to guard communications links—like the telephone company.

"We got soldiers from the East Coast, New Englanders, and they had a completely different accent. Then we got some from Louisiana and they were different. Then we got a bunch from Chicago—we couldn't even understand them hardly."

During the war years, air raid drills and alerts became a common occurrence throughout the states.

"One night there was a red alert," Hall recalled. "A yellow alert was a little shaky, but a red alert—you got on your toes.

"We had a red alert and here came a bunch of soldiers with flashlights. They used the flashlights for the girls answering the signals, and making dates at the same time. I tell you there was more dating going on with a lot of single women, and married women too, on hte Harbor," Hall said, letting out another big laugh.

IN 1952, WHEN her youngest daughter, Beverly, now a teacher at Simpson Avenue Elementary, was five years old, Hall began the first of her many decades of work in the library.

"It was an old building, and up on the third floor at the end of the hall was what they called a library," Hall said.

The library was just that, the end of the hall and the only door leading to the fire escape outside.

"There weren't very many (books) and they were all discards that people had dumped," she said.

When Hall was volunteered for the position of library chairman, she didn't have any experience and didn't really know what to do.

"It was a title with nothing with it, but boy, I took it very seriously," she said.

Hall's husband, Alexander, made shelves to hold the few library books that before then had simply been stacked on the floor.

Hall also lobbied hard for money to expand the meager selection of books.

"I used to go and talk with the PTA people when they had a little money and tell 'em their kids would never get out of A.J. West if we didn't get library books," she said. "And the PTA gave very, very generously and we built it up from there."

In 1952, Hall could order a good, hardcover book for $2. When you ask her about the price of books today, Hall lets out a groan. "But they do get a discount," she says.

For the first 10 years, Hall worked for free, spending her time with the children, mending, cataloging and ordering the books.

The next 10 years, Bessie worked as a paid librarian as the "library" was moved into a new building and its own separate room.

"I worked 10 years for free, 10 years for wages. After the (second) 10, they gave a party and gave me a watch—I was back in September."

AND SHE'S BEEN back every September since, her love of books and children driving her to return the schools.

"Kids grow on you, you know," Hall said.

With new books coming out all the time—for children as well as adults—Hall continues to read books commonly reserved for youth.

"You gotta read them to be able to peddle them," she said.

One of the biggest phenomenons of the children's publishing industry in recent years has been the "Goosebumps" series by R.L. Stine.

Hall's read them, too.

"I read one of them and my hair stood on end," she said. "I thought, boy I don't know about this for kids."

So Hall asked some youngsters who read the books if the books scared them.

"They said: 'Oh, kinda. Yes,' " Hall recalled. "Well does it bother your sleeping?" she asked them. " 'Oh, no,' they said. 'You know, Mrs. Hall, they're just make-believe. They are not true books.' "

Though they may never be compared with the classics of modern literature, at least they get kids into reading, Hall argued.

"That's not the best of literature, really," she said. "Sometimes if kids get hooked on a book they will branch off into better books."

According to Hall, those better books would include the "Little House on the Prairie" books written by Laura Ingalls Wilder.

In her many years in the library, Hall has come up with many ways to get youngsters to read.

"There's all kinds of tricks to get kids to read," she said. "The last time I was at (A.J.) West I asked for four or five volunteers to take a book and read it and tell me next time if they liked it or not.

"You see, when you ask their opinion, they feel they are really contributing something," Hall said.

In her spare time Hall reads books by Danielle Steel, J.A. Jance and others.

"When I had time I started reading fiction. Boy, if I'd have had them when my husband was alive I could have made it much more interesting for him," she said with a big grin on her face.

"Well, honest to goodness, what they put in those books, poor, old Hall was long gone," she said.

HALL'S WORK HAS not gone unnoticed. She has received Golden Acorn awards from both the Aberdeen and Montesano school districts and she was nominated for The Daily World's Citizen of the Year award this year.

But the rewards Hall treasures most are the memories given her by the children.

"When you work with kids you get paid back 100 times for your effort," she said.

When Hall was asked to make a speech after receiving the Golden Acorn award in Montesano many years back, she was asked to say a few words.

"I thought: 'Oh gee, what am I going to say?'" Hall recalled. "Then I remembered what one of my daughter's first grade kids had said to me. He put his arms around me and said, 'I love you Mrs. Hall, and you smell nice.'

"That was my speech and I got a standing ovation," she said. "You're rewarded every day when you work with kids."

A.J. West Principal Bill O'Donnell applauds Hall's work.

"She's always telling them to shut off the TV and get their noses in a book," he said.

"To this generation she's kind of like a grandmother," O'Donnell said. "She'll get in the hot lunch line with the kids and sit down at the table and eat with them."

According to O'Donnell, the kids also get a glimpse of Hall's sharp mind and quick wit.

"She'll joke with them just like she will with the adults," he said.

Hall refers to O'Donnell, a Montana native, as the "Montana Sheepherder." O'Donnell counters, calling Hall "The Relic."

"He called me 'The Antique' and I said antiques increase in value every year," Hall said. "Well, that was sticking a pin in his balloon. So now he calls me 'The Relic.' "

AFTER ALL THESE years, Hall shows no signs of letting up. She said she will be busy these next few weeks at the library—it's inventory time.

She's also thankful for her family.

"I've been very blessed with two supportive daughters and two supportive grandkids," she said.

After a brief pause, she added: "Oh, and my son-in-law likes me too."

So do a lot of others, Bessie—so do a lot of others.